As someone who regularly trawls through Hansard in search of references to ESG, I can safely say the term has not exactly made its way into the vernacular of Parliament (between the election and March, it was mentioned twice in the Commons). While related themes like sustainability, biodiversity, and net zero are familiar ground, ESG itself remains somewhat misunderstood. That said, in March, Alex Baker, MP for Aldershot, has managed to put ESG firmly on the agenda, gaining the attention of industry, civil society, MPs and Peers. In an open letter backed by over 100 Labour parliamentarians, she called for a “rethink of ESG mechanisms that often wrongly exclude all defence investment as ‘unethical.’”

At first glance, Baker’s letter might seem like a straightforward appeal. But the relationship between ESG and defence is not new and operates on multiple levels.

Why is this conversation being had?

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, rising concerns over national security, and the Trump administration’s unpredictability and repeated attacks on NATO, have all triggered a fundamental rethink of defence policy across Europe.

In the UK, Rachel Reeves used the Spending Review to commit to increasing defence spending to 2.6% of GDP by 2027, with a further ambition to reach 3% at some point during the next parliament. In March, the EU Commission announced “Rearm Europe” or “Readiness 2030”, which the Commission has estimated could mobilise €800 billion to strengthen its collective defence capabilities. Even Germany, long bound by strict fiscal rules, has seen a historic shift, changing spending constraints to free up billions more euros for its armed forces.

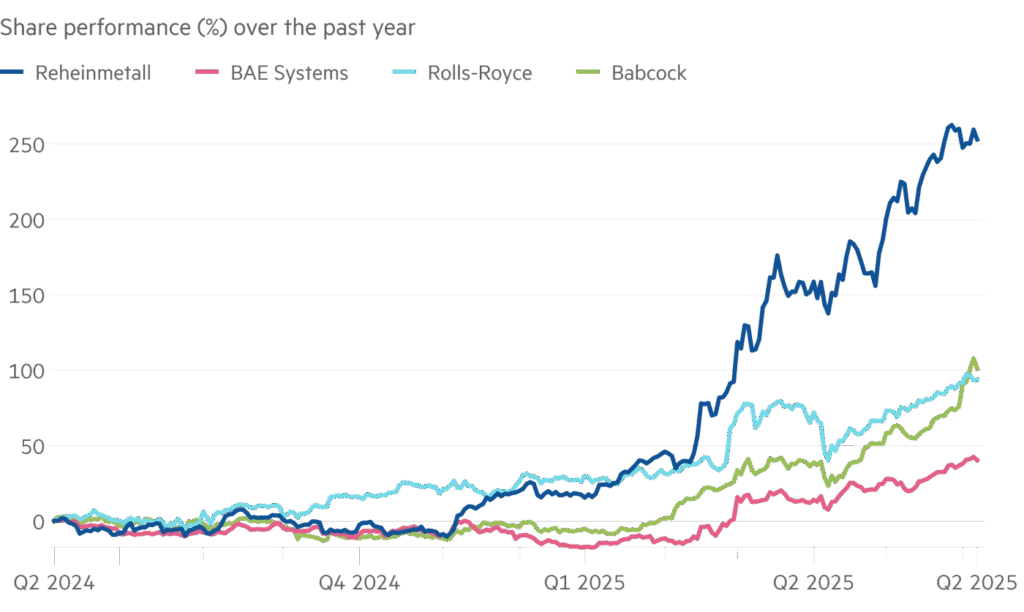

Unsurprisingly, European defence stocks have soared, buoyed by expectations that this wave of spending will benefit the sector. Much like during the Cold War, defence investment is back in fashion, and this time, it is being framed not just as a matter of national security, but as a strategic economic and ethical choice.

So, what exactly is ESG?

According to PwC, ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) is a framework for businesses to evaluate their impact on the environment and society, as well as the strength of their internal governance. It covers issues like carbon emissions, labour rights, and corporate governance, areas that often fall outside traditional financial reporting.

Over the past decade, ESG has become an influential lens through which investors evaluate risk and opportunity. But in recent years, it has also faced backlash. Morningstar has tracked a noticeable cooling in ESG enthusiasm, UK fund inflows have slowed, and US funds have seen outflows. Notably in the United States, ESG has become a political target, with Trump branding it a “way to attack American business” and dismissing it as nothing more than “woke capitalism.”

But the rhetoric does not match reality. The investment industry has said that ESG regulations have not prevented major investors from backing defence companies. In fact, most UK pension funds incorporate ESG principles and yet remain heavily invested in firms like BAE Systems and Rolls-Royce, both of which hit record share prices on 27 May.

Source: Financial Times, June 2025. Data provided by LSEG

What is often missed in the public debate is the distinction between ESG integration and more restrictive “ethical” or “values-based” investing. While ESG is about managing financial and non-financial risks, ethical investing often involves screening out entire sectors, such as defence, based on personal or moral preferences. These exclusions tend to apply only to a limited number of retail funds.

Where ESG frameworks do draw firmer lines is around controversial or internationally banned weapons, such as nuclear arms, landmines, cluster munitions, and chemical or biological weapons. These exclusions, often driven by legal and reputational risk, were further reinforced after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Importantly, they typically target specific weapon types rather than the defence sector as a whole.

Clarity from the regulator

On 11 March 2025, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) issued a statement clarifying that “there is nothing in our rules, including those related to sustainability, that prevents investment or finance for defence companies”. The regulator was clear: it is up to individual investors and lenders to decide whether to provide capital to the sector. Torsten Bell MP, the new pensions minister, echoed this view, affirming that “in the vast majority of cases” UK pension funds already do invest in defence.

The UK’s Sustainability Disclosure Requirements (SDR), introduced in 2023, aim to bring greater transparency to investment products labelled as sustainable. The defence sector is not explicitly mentioned under SDR, leaving room for different approaches.

What does Alex Baker want?

Despite the political noise, capital is not fleeing the defence sector – at least not at the top end. According to Morningstar, 32% of UK-based ESG funds they rate still have exposure to the defence sector. In a recent article, the FT noted that “funds looking to invest in the defence sector could look to rebadge themselves as ‘ESSG’: environmental, social, security, and governance funds.” However, they questioned whether given the prevalence of ESG, such a rebadging would in some sense be no more than semantics.

Nonetheless, what Alex Baker is really drawing attention to is not the major defence primes like BAE, the ESG debate she’s trying to ignite is much more specific – the smaller firms in the defence supply chain. Many of these SMEs are struggling, not because of ESG per se, but because of a broader set of financial barriers.

In a joint report published by her and Luke Charters MP on 9th July, they argue that ESG concerns are “only the tip of the iceberg” when it comes to the financial challenges facing defence SMEs. The report sets out how smaller firms in the sector are routinely overlooked by traditional lenders and investors, not due to outright policy exclusions, but because of a mix of risk aversion, operational complexity, and a lack of understanding about the nature of the defence supply chain.

Key barriers identified include difficulties in opening and maintaining bank accounts, securing insurance, and accessing working capital or long-term investment. Many lenders are deterred by the perceived unpredictability of defence contracts, a lack of financial track record among SMEs, and an overreliance on public procurement. Even where firms do secure contracts with the Ministry of Defence, they often struggle to leverage these into finance, due to slow payment cycles and limited collateral.

The report also highlights how inconsistent interpretations of ESG, especially around dual-use technologies, create additional uncertainty for both lenders and borrowers. In some cases, this results in automatic exclusion, despite the absence of regulatory restrictions.

Ultimately, Baker and Charters are calling for a more practical and coordinated response, from government, regulators, and the finance industry, to ensure that viable, responsible defence SMEs are not left structurally underfunded. This includes clearer guidance from regulators, better use of public finance institutions, and the development of specific financial products that reflect the realities of operating in the defence sector.

What's next?

The conversation around ESG and defence is definitely not over.

Alex Baker MP has helped open the door to a more pragmatic debate about how ESG can be applied more thoughtfully. At its core, ESG is about identifying and managing long-term risks, something that should align naturally with national security and resilience.

The task now is not to abandon ESG, but use it better: with clearer definitions, more consistent disclosures, and a better grasp of the defence sector’s role in a sustainable and secure future. Done right, ESG doesn’t have to be a barrier. It could be part of the solution.